2019 Election Final Forecast

In almost every Israeli election, we have an “election-day surprise.” The polls say one thing - the results come out different. Can we do better?

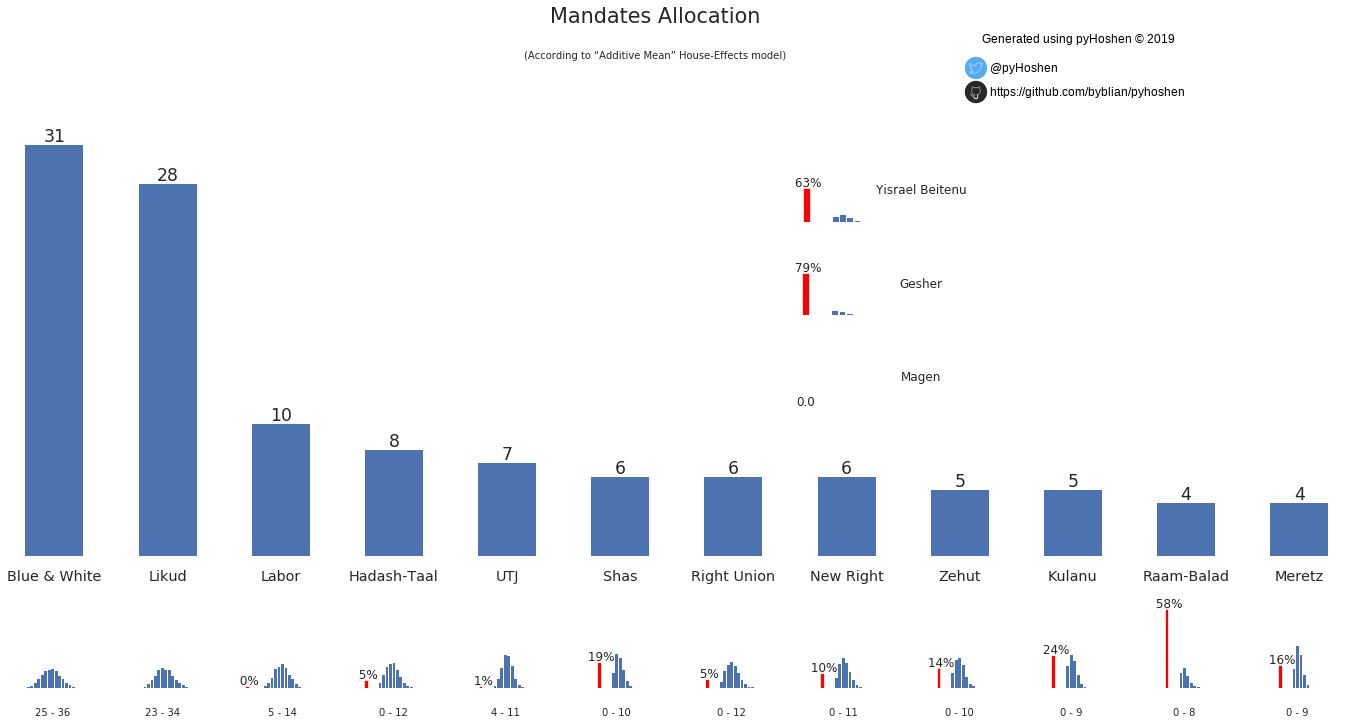

The final forecast has Blue & White doing slightly better than the Likud. Due to the many parties, the high threshold, and the lack of polls up to election day, the uncertainty is high. The only thing that we can say with relative certainty is that the four parties - Likud, Blue & White, Labor, and United Torah Judaism - will be in the next Knesset, while all the rest have some probability that they might fail to make the threshold. Based on the current polls, Likud might get anywhere between 23 and 34, while Blue and White somewhere between 25 and 36. The exact distribution is given below the party mandate bars. The chances any particular party will fail to pass the threshold is given above the small red bar next to it. The range (such as 23 - 34 for Likud or 25 - 36 for Blue and White) is the range of mandates in the 95% confidence interval for the party.

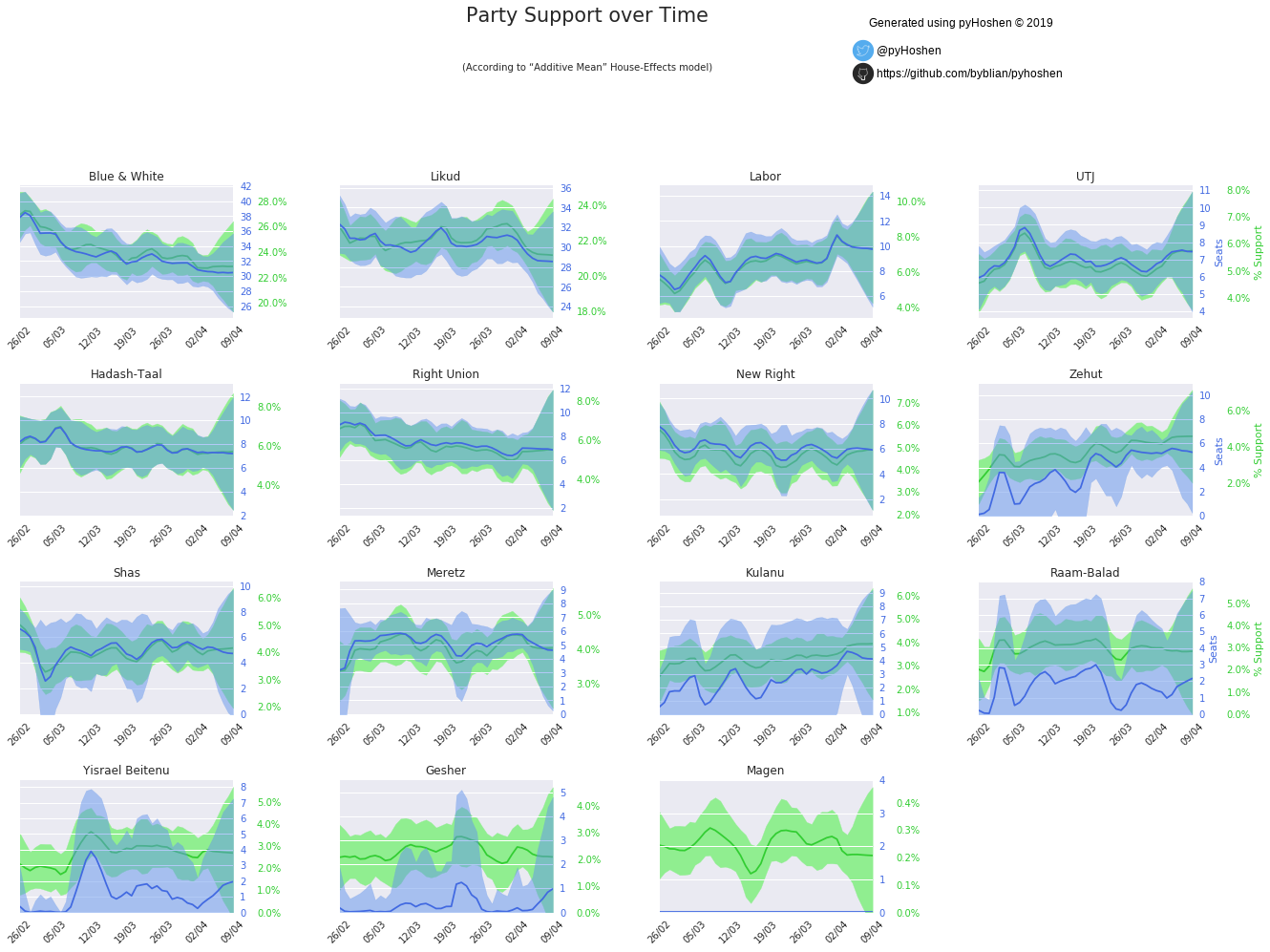

We can see how the support levels for the various parties as well as the uncertainty evolve in the graph below (especially during the “poll blackout” period):

To deal with all the uncertainty, the model chooses a representative sample that it believes is the closest to the average. We are now in a poll “blackout” until election day. During this time a lot can happen. In 2015, the very last polls appeared to indicate a last minute game-changer in favor of Zionist Union and political commentators suggested Likud was certain to lose. This directly supported the Likud’s message throughout the campaign and as a result, many voters for smaller right-wing parties apparently decided to change their vote at the last minute to Likud. In contrast to the last-minute polls, Likud won by a big margin leading to that year’s “surprise.”

Today, it appears that the polls are more stable - there does not seem to be a last-minute game-changer as such. Zehut’s odd video may be considered as such for better or worse but its effect is probably limited to Zehut. It does not appear to directly affect the major parties - Blue and White or Likud. Possibly, these considerations are already factored into the polls.

The primary problem this year is that we have to contend with multiple parties that border the threshold. The model expects that Gesher has an 80% chance of not passing the threshold, Yisrael Beitenu has a 63% chance of not passing the threshold and Raam-Balad probably won’t pass the threshold with a 58%. From the parties that the model believes have a higher chance of making it, there is still uncertainty: Kulanu has a one in four chance of not making it, Shas has a 1 in 5, Meretz has a 1 in 6, and Zehut a 1 in 7 chance of not making the threshold.

To give an idea of the way the various party mandates might vary, here are the top 5 potential outcomes (out of the 5000 samples):

| Blue & White | Likud | Labor | Hadash-Taal | UTJ | Shas | Right Union | New Right | Zehut | Kulanu | Raam-Balad | Meretz | Magen | Gesher | Yisrael Beitenu |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 31 | 28 | 10 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 30 | 29 | 10 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 8 | 6 | 5 | 6 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 31 | 29 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 5 | 7 | 7 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 31 | 29 | 9 | 9 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 4 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 32 | 30 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 5 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

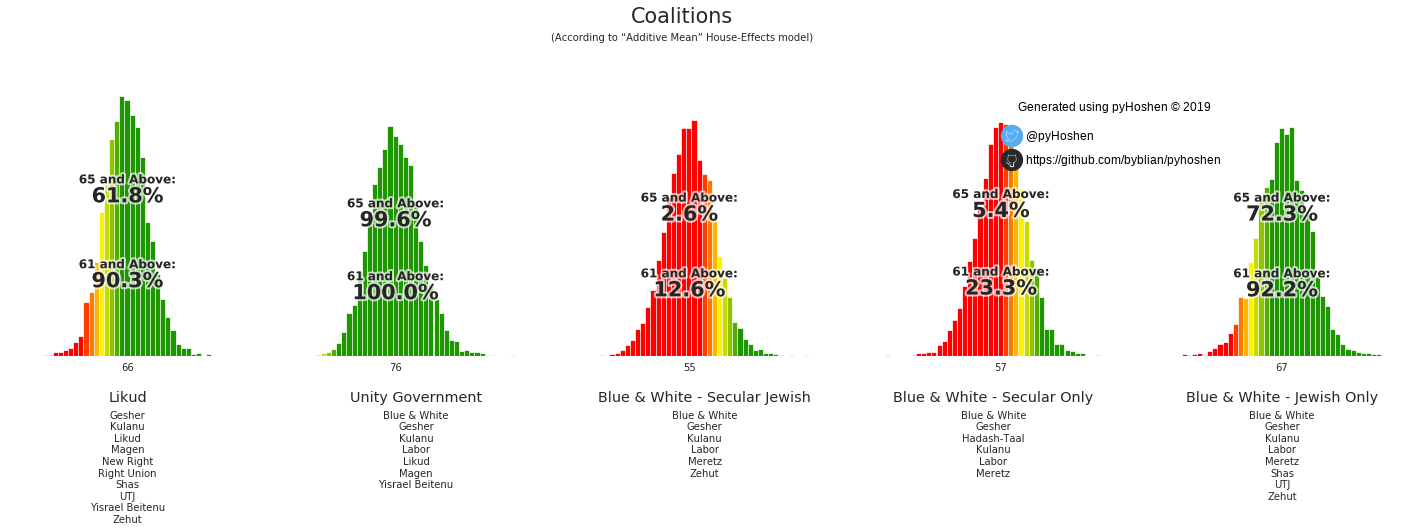

Coalitions Forecast

Even if one or two parties do not make it, the coalitions that can form are more certain. In 2015, Netanyahu formed a very narrow government of 61 MKs. This seems almost certain to be possible here – there is a high chance of approximately 90% that Netanyahu will be able to form a narrow right-wing government, and a good 60% chance that Netanyahu will be able to form a stable government of 65 MKs or more. In fact, the average right-wing Netanyahu coalition is expected to be 66 MKs. If such a stable right-wing coalition does form, the smaller parties should hope to achieve at least 6 mandates - which will force Netanyahu to give in to any of their demands, while parties that get 4 or 5 mandates would have much less bargaining power.

Blue and White has similar chances for forming a “Jewish only” government, on paper. But it seems unlikely that the ultra-orthodox parties will join Blue and White with their heavy Yesh Atid representation - Lapid is one of the candidates for Prime Minister and the party platform is heavily based on Yesh Atid’s secular platform. A unity government is almost certainly possible - the question is whether Netanyahu wants it. (Blue and White is considered here as a whole for the purposes of a unity government).

About the Model

In the US, as well as elsewhere, Bayesian statistics and MCMC modelling have been used to predict the elections by sites such as Nate Silver’s 538 and others. It worked very well in 2008 and 2012. In 2016, 538 still “missed” but estimated that Trump had chances of about 30%.

I present here the final forecast of a similar model adapted to Israel, using MCMC techniques. The model is open-source and you can learn how to run it yourself and read the technical details in a separate post. In short, this model is an elaborate polling average (a “poll of polls”) that takes into account party correlations and pollster bias (“house effects”). It is based on 58 polls taken since February 21, 2019, the day that the party lists were finalized. You can see the full list of polls here. Three polls published since Feb 21, 2019 besides those 58 were not included because insufficient data was published. The results are based on the distributions in 5000 samples that were computed.

The model’s strengths are:

- It is able to account for specific pollster bias or “house effects” - if one particular pollster consistently favors a particular party over the average, the model will determine this. House effects may be a result of intentional favoritism towards some parties (for example, if the firm also acts as the political party’s internal pollster). But it may also be unintentional - a result of incorrectly weighting demographic factors, the phrasing of the polled questions, etc.

- It is able to account for various ways that small parties do not make the threshold - the model is used to generate thousands of samples that match the polls. In any sample, some of the parties might make the threshold and some not. These combinations are taken into account when considering the final coalition chances.

- It is able to account for correlations between parties - the model uses the polls to determine which parties are correlated to other parties. For example, if it determines that Hadash-Taal and Raam-Balad are negatively correlated, the results will reflect that. If a particular sample has Hadash-Taal doing better than average, Raam-Balad would do worse than average, and vice versa.

But the model also has its weaknesses:

- It cannot account for changes during the poll “blackout.” This is the last few days of the election in Israel, when polls may not be published. For example, suppose a video is released during the weekend before the election while the poll blackout is already in effect. If this video ends up causing some voters to change their minds, the model has no way to foresee such an event. (Did anyone?)

- It cannot account for systematic pollster bias present in all pollsters. That is, if all pollsters are polling a specific party below or above its actual support level, the model would be based on the average poll result. It does not attempt to adjust or correct this systematic error.

- It does not attempt to account for undecided voters and does not adjust for likely voters. For both of these, it depends on the pollsters’ own adjustments.

Go vote!